On Feb. 16, 2020, Racquet Press Reporter Melissa Touche wrote an article addressing La Crosse’s history as a sundown town.

The article featured Sociologist James Loewen who passed away in 2021 and University of Wisconsin-La Crosse Alumni Jennifer DeRocher who works at the La Crosse Public Library.

The Racquet Press revisited this article with Associate Professor at UWL, Richard Breaux and Physician at Emplify Health (formerly known as Gundersen Health), Michael Ojelabi.

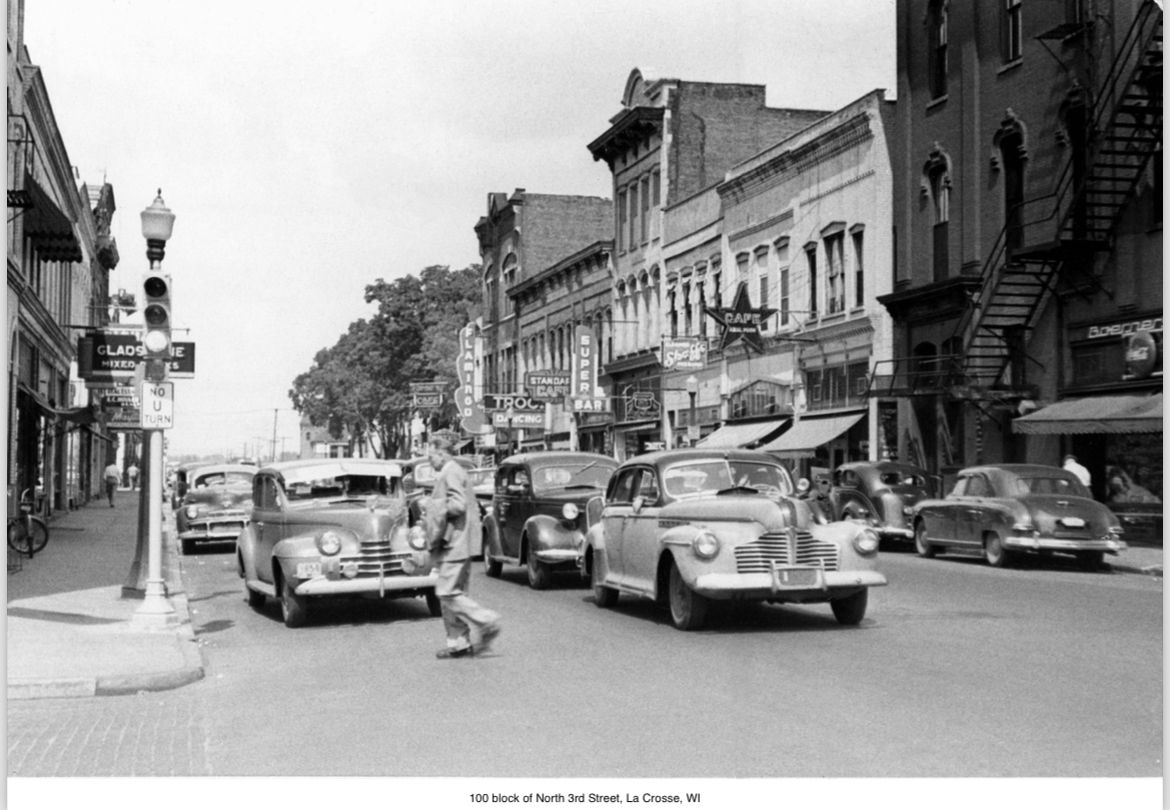

Breaux started by giving the traditional meaning of a sundown town. He defined them as towns that had ordinances in the United States that restricted specifically Black people to people of color in general, depending on the town, where those people could live.

“The name sundown town comes from the idea that people were able to work in a town and be in a town in the daytime but by the time the sun went down they were expected to not be within the city limits, that’s the name,” said Breaux.

Breaux explained that research done by DeRoacher and influenced by Loewen’s work revealed how La Crosse could fall under the sundown town category.

“He talked about towns that weren’t officially sundown towns but were towns that discouraged Black people from living in them and so La Crosse was kind of more of that type of a town or city than a formal sundown town with a policy,” said Breaux.

He went on to further explain the reasons for La Crosse’s interpretation as a sundown town.

“Essentially… it was almost impossible for African Americans or Black people in La Crosse to find a job outside of barbering, shoeshine, sort of personal service type work for or to White people,” said Breaux. “In that sense, one had to be self-employed and/or if you were employed, you were restricted in what types of jobs you can have. Why stay if you can’t get a job or no one’s hiring?”

Breaux’s statement fell in line with some historical resources shared on DeRoacher’s blog on La Crosse Public Library that recounts a La Crosse Tribune story reporting on the experience of a Black man named Haywood Talbert, who was chased out of town.

The blog states, “The way that this article is printed mocks Talbert’s speech patterns, which in turn mocks the incident as a whole. In attempting to confirm this story, I found that there was a man named Hayward Talbert in the 1924 City Directory, listed as a shoe-shiner. He was only listed in the one directory.”

At UWL, Breaux teaches a hip-hop, culture, race and gender course, African American studies and race and urban conflict. Breaux said that he teaches students about sundown towns every semester as a way to get them to understand how racism worked in the Upper Midwest.

“Most people when they think about racism… they think about overt racism, they’re not necessarily thinking about more subtle forms of racism when people are intentionally excluding you from work but not saying anything or there’s nothing written. But those more subtle forms of racism are really what people practice outside of the South,” said Breaux.

Breaux’s words were supported by Loewen’s research that pointed out that sundown towns were sparse in the South and many sundown towns were and are in the Midwest, with many undiscovered in Wisconsin.

In the 12 years that Breaux has been at UWL, Breaux recounts being present for some of the hate and bias incidents that have occurred over the years. He mentions being around during the Confederate flag and KKK drawing incidents.

He appeared on several panels related to those incidents describing them as “the way that academic environments often handle incidents like that… to make a statement.”

Breaux expressed his opinion regarding his hopes for the University to do more beyond the panels for both affected students and faculty.

He said, “There might be a hate bias report submitted, there might be some discussion with someone who is specifically targeted if the incident is directly targeted at an individual. Otherwise, I don’t know that there’s a lot else that happens.”

Breaux added, “As an employee, no one checks on your well-being… I don’t know how much discussion happens with respect to checking to see that employees and their families are okay.”

Breaux mentioned that one area that UWL had changed significantly was its employment of black officers in the campus police force. He said that it did not exist when he first got to UWL, calling it a– “a post-covid, post-George Floyd phenomenon.”

When asked about the lasting impacts of La Crosse’s sundown history today, Breaux discussed the role of the city’s current demographics and the institutions that operate within it. He referred to the Affirmative Action policy struck down in 2023 as a significant influence on demographics.

“A lot of people are misinformed on what affirmative action was or was not. People believed it was and saw it as a quota that said you had to have a certain amount of representation… but that never was what affirmative action was meant to do. Affirmative action was really designed to prevent employers or schools or other places of business from discriminating against people it had a history of discriminating against,” said Breaux.

He continued, “The idea was, if you’re no longer discriminating against those people your employees or your students or your customers should look like the changing demographics of a city and so if they don’t look like the changing demographics of a city then you probably haven’t done anything to change your business practices.”

Ojelabi is primarily a physician but also handles a real estate business with his wife. He moved to La Crosse for a job and has been here for thirteen years.

The Racquet sat down with him to discuss the negative stereotypes perpetuated on Black individuals, which are used to exclude them from predominantly White neighborhoods today and contribute to the stigma surrounding predominantly Black neighborhoods.

Ojelabi mentioned that in his and his wife’s years of renting out their property, they have had negative experiences with different races, and it wasn’t exclusive to one.

“As individuals, it’s also important that individual conduct will not be interpreted as all,” said Ojelabi.

Ojelabi explained how the negative stereotypes attached to predominantly Black neighborhoods were underserved and were a measure of face and not a measure of individual conduct and behavior.

“Relatively, African Americans are more likely to rent than compared to Caucasians per population so if you have somewhere [where] there are families that are struggling and there are more people living in the unit and some of those people don’t behave well then it basically becomes ‘they are all like that’ kind of situation which might not justify the situation,” said Ojelabi.

“Human beings are always a work in progress and it’s important not to fixate on the things that happened in the past,” said Ojelabi. “But at the same time, the things that happened in the past can really shape what’s going on in the present.”