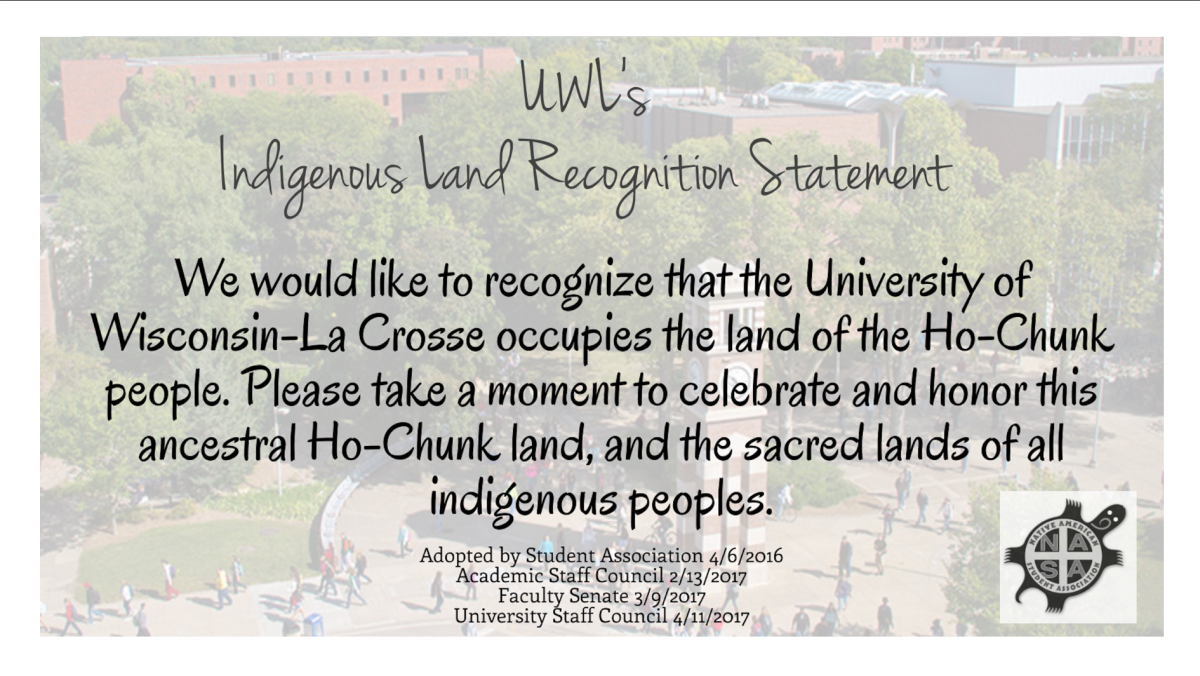

In 2017, the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse officially adopted the Indigenous Land Recognition Statement.

It reads, “We would like to recognize that the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse occupies the land of the Ho-Chunk people. Please take a moment to celebrate and honor this ancestral Ho-Chunk land, and the sacred lands of all indigenous peoples.”

The statement was written by members of the Native American Student Association (NASA) in 2016 in hopes that it would reaffirm the university’s dedication to diversity and inclusion, honor indigenous peoples and educate those who listen to the statement.

Now, current members of NASA are hoping to have the statement rewritten because they believe the current statement is too general and missing key information about how the Ho-Chunk people were forcibly displaced from this land.

Jolani Lujan, a member of the Ho-Chunk Nation and a big reason NASA was revived at UWL, said, “Land acknowledgements are meant to tell people the history behind these institutions and to acknowledge the fact that these institutions wouldn’t exist if we didn’t push these people out.”

Lujan brought up the La Crosse Public Library’s Land Recognition Statement and how they collaborated with the local Ho-Chunk community to create what she described as a solid land recognition statement.

It reads, “The La Crosse Public Library acknowledges that it occupies the ancestral lands of the Ho-Chunk, who have stewarded this land since time immemorial.

The city of La Crosse occupies land that was once a prairie that was home to a band of Ho-Chunk. In 1830, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act in attempt to forcibly and often violently remove Indigenous peoples from their ancestral lands located east of the Mississippi River to occupied territory west of the river. Throughout the 1830s and 1840s, the Federal Government conducted a series of six attempts to forcibly remove local Ho-Chunk by steamboat via the Mississippi River to reservations in Iowa, northern Minnesota, southwest Minnesota, South Dakota, and finally to Nebraska. The historic steamboat landing where this took place is now Spence Park in downtown La Crosse.

However, many of La Crosse’s Ho-Chunk found their way back to their homeland and eventually the federal and local governments moved on to new strategies to eradicate Indigenous folks and culture from the newly established United States of America. As of 2016, Wisconsin was home to over 8,000 members of the Ho-Chunk Nation, about 230 of whom live in La Crosse County.”

The library’s statement gives historical context that allows people to understand why this land no longer belongs to the Ho-Chunk people. Lujan mentioned that a lot of students on campus might hear UWL’s statement and not know any of the history behind it, including the fact that the Ho-Chunk people were forcibly removed.

“People hear the land acknowledgement and they’re like, ‘Oh just something else we have to listen to.’ What does that mean though? Why are we doing this though?” Lujand said. “That’s why the rewrite is important because it will help give the students the education of why this is important.”

Tamiaya Cornelius, NASA president and member of the Oneida Nation, said, “You can’t know what you don’t learn. At this point the only thing we can do is try to educate people.”

Cornelius also mentioned that this time it should be the university leaders drafting the land recognition statement, not the NASA students.

“At the end of the day we want them to acknowledge it themselves and not have us doing the emotional labor of writing it. Because what are we acknowledging? We lived it,” said Cornelius.

Cornelius plans to work with Chancellor Beeby and the local Ho-Chunk community on this initiative with a goal of seeing it complete within the next year or so.

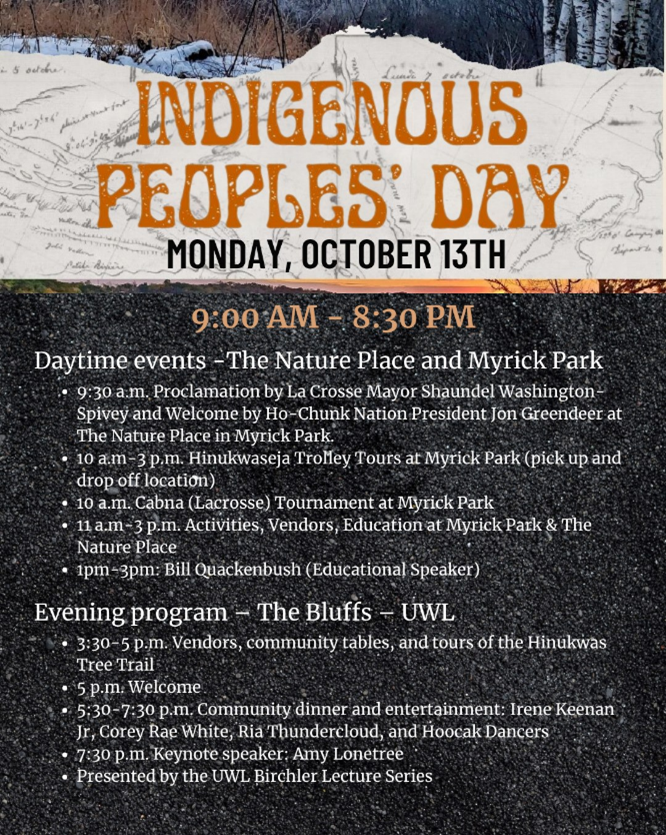

On top of the rewrite, Cornelius and Lujan brought forward a resolution to have a Ho-Chunk flag permanently displayed on campus, just in time for Indigenous People’s Day, which will be held on Monday, October 13, 2025. This resolution was passed by the Student Association on Wednesday, Oct. 1, 2025.

Since this resolution has passed, they will now begin the process of pushing for a revision of UWL’s current land recognition statement.

“What’s done is done and it can never be undone,” Cornelius said. “The least [the university] can do is acknowledge that and make sure it is known. We don’t want our history to be erased… and that broad, general statement just isn’t going to cut it.”

For those who want to learn more about Native American history and culture, Indigenous People’s Day has programming open to anyone who is interested. The Hinukwas Tree Trail on campus and Hear, Here stops in the community are also great ways to learn about the Ho-Chunk people.

Cornelius said, “We would love for students to come because the only thing we want to do is educate and build a community. Anyone is welcome that wants to learn more.”