Explained: The Clery Act

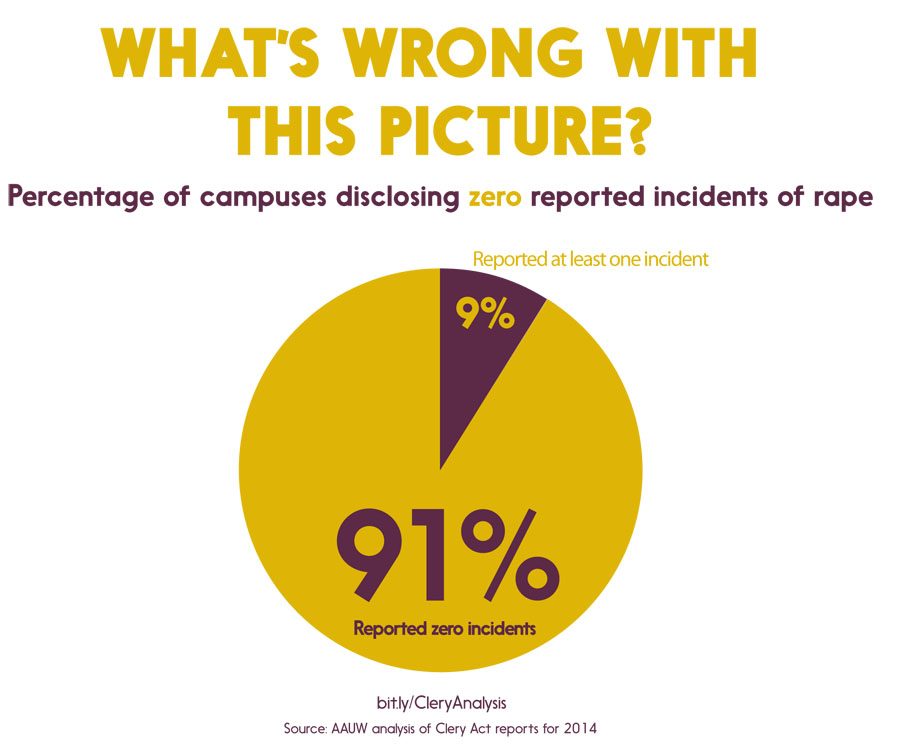

91 percent of college campuses reported zero incidents of rape in 2014. Photo retrieved from the AAUW.

October 9, 2019

In the dormitories of Lehigh University Pennsylvania, on April 5, 1986, freshman Jeanne Clery was raped and murdered by fellow student Joseph M. Henry. In the years following her death, and upon further investigation, Clery’s parents discovered what they felt was a significant lack of statistical crime rate reporting from the University.

In response, they became advocates and pioneers of what is now known as the Clery Act; a policy designed to hold Universities accountable for disclosing their respective crime rates to students and parents.

Under the Jeanne Clery Disclosure of Campus Security Policy and Campus Crime Statistics Act, universities are responsible for making public any altercations or crime that happens on their grounds every year. According to an executive summary of the act under the Federal Register, updated during October of 2014,

“The Clery Act requires institutions of higher education to comply with certain campus-safety and security-related requirements as a condition of their participation in Title IV HEA Programs [Federal financial assistance programs].”

On March 7, 2013, the act was updated to include the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act. “Notably, VAWA [Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act] amended the Clery Act to require institutions to compile statistics for incidents of dating violence, domestic violence, and stalking, and to include certain policies procedures and programs pertaining to these incidents in their annual security reports.” All of this from the same federal registry.

Throughout its 19 year lifespan, the Clery Act has undergone several amendments to accommodate changing university lifestyles, however, it has not seen much change in its ability to maintain an accurate and consistent trend of data.

The terms described in the Clery Act disregard certain specifics in fundamental definitions, which allows for inconsistency in reporting practices.

According to Kristen Lombardi, reporter for the Center for Public Integrity, discrepancies in reports are the result of a number of loopholes; of which, include a lack of concrete classification of sexual assaults, lack of communication with those who have sexual assault information — such as police departments, and confusion over who is to be defined as report-mandated officials.

As a result, schools are able to classify criminal activities on campus as non-threatening events that don’t require attention on the annual report.

Under technical terms, schools are required to have crisis-service programs available to students. Theoretically, these services are included in the mass of those who must report to school officials for the purpose of collecting Clery data, however, this isn’t always realized:

“A Center survey of 152 crisis-services programs and clinics on or near college campuses requested incident numbers over the past year: 58 facilities responded with hard statistics,” said Lombardi. “Available data suggest that, on many campuses, far more sexual offenses are occurring than are reflected in the official Clery numbers.”

In this past year’s Annual Security Report (ASR), the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse reported a total of five rape cases and seven fondling instances, as well as two total cases of domestic violence and seven cases of stalking.

Written next to asterisks underneath the report chart on page ten of the ASR, are the technicalities the chart abides by. Of those is a policy on unfounded crimes: “In accordance with new guidance from the Department of Education, ‘Unfounded Crimes’ are reported in Aggravate.” By definition, an “unfounded crime” is a crime with no evidence and is therefore without means to convict.

According to the UWL statement on the Act, Clery-Crimes are defined under the following categories: Murder & Non-negligent manslaughter, Negligent Manslaughter, Forcible Sex Offenses, Non-forcible Sex Offenses, Robbery, Aggravated Assault, Burglary, Motor Vehicle Theft, Arson, Weapons Law Violations, Drug Law Violations, and Liquor Law Violations.

This means that any criminal activities that are reported but aren’t taken to court, are not displayed in the immediate findings table on the ASR. This includes sexual assault cases that go unvalidated or provide a lack of evidence.

In the case of one woman— who for the sake of identity protection is referred to as Ella— after reporting a rape to both hospital officials and police officers, she was sent home.

According to the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, Ella was living with autism and was having trouble communicating her circumstances. She claimed rape, and upon follow up, the man who she accused admitted to having sexual intercourse with her, but claimed it was consensual. No initial examination was done, and after a period of time, all opportunities for evidence disappeared.

According to TIME reporter Charlotte Alter, this is a common occurrence in rape cases. To acquire hard evidence for a rape case, the victim must submit themselves to undergo an examination to look for biological remnants of a rape.

These biological remnants make up what colloquial language refers to as a rape-kit. “Getting a rape kit collected is no picnic. The process can last up to four hours, and involves getting poked, prodded, swabbed and photographed in exactly the places a rape victim would have been violated in an attack,” said Alter. This process has to be done within a small window before important evidence becomes undetectable.

However, even after the process is completed, thousands of rape-kits never see the court. “Only around 15 percent of rapes recorded by police as crimes in 2012/13 resulted in rape charges being brought against a suspect. Two-thirds of rape complaints dropped out of the criminal justice system before they were sent to prosecutors. And this was not because a suspect had not been identified – in the majority of cases, the identity of the alleged rapist was known,” said Melanie Newman, a reporter for the Bureau of Investigative Journalism.

Because many sexual assault allegations are never brought to court, they go unrepresented in population reports, such as the ASR of the Clery Act.

Lombardi also mentioned in her statement, “There’s also been misclassification of sexual assaults. Schools can wrongly categorize reports of acquaintance rape or fondling as “non-forcible” sexual offenses — a definition that should only apply to incest and statutory rape.” Which also contributes to the accuracy of university statistics.

In light of events taking place on campus this year, some UWL students have taken a stand to demand accountability of the University of La-Crosse officials and to solidify the testimonies of those who were not granted validity under the report in the ASR.

Kendra Whelan, a senior at UWL, said after reading this year’s report she felt concerned:

“I’m just really concerned with Title IX [act passed to prohibit discrimination on the basis of sex] on campus and whether or not we are compliant with federal law, including the Clery Act. I’m very concerned with how low our reporting numbers are, given like the one to four and the one to five statistics— having five reported rapes on Campus last year— is ridiculously low,” said Whelan.

“I just want to know what the University is going to do to help improve trust in their process. Because I think very clearly at this point the reason students aren’t coming forward and the reason they aren’t reporting is that they don’t feel like they can trust them. You know, we hear all of these stories about these men who are very clearly violating the conduct policy at UWL, and they just go free, they’re found not in violation. So how are students supposed to trust them [University Officials], how are students supposed to believe that they will support them if they come forward? It doesn’t make any sense and I want to know what they are going to do to rebuild that trust.”