In 1923 the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse, known as the La Crosse Normal School at the time, hosted its first official homecoming. According to the Oct. 17, 1923 edition of the Racquet, the eventful weekend included parades, a pep rally, banquets, a bonfire, a dance and the football game in which UWL beat Lawrence University.

“Old timers here claim that never before was such spirit shown by a team and student body,” said the 1923 Racquet Press. “The school spirit which was manifested was the best in the history of the school.”

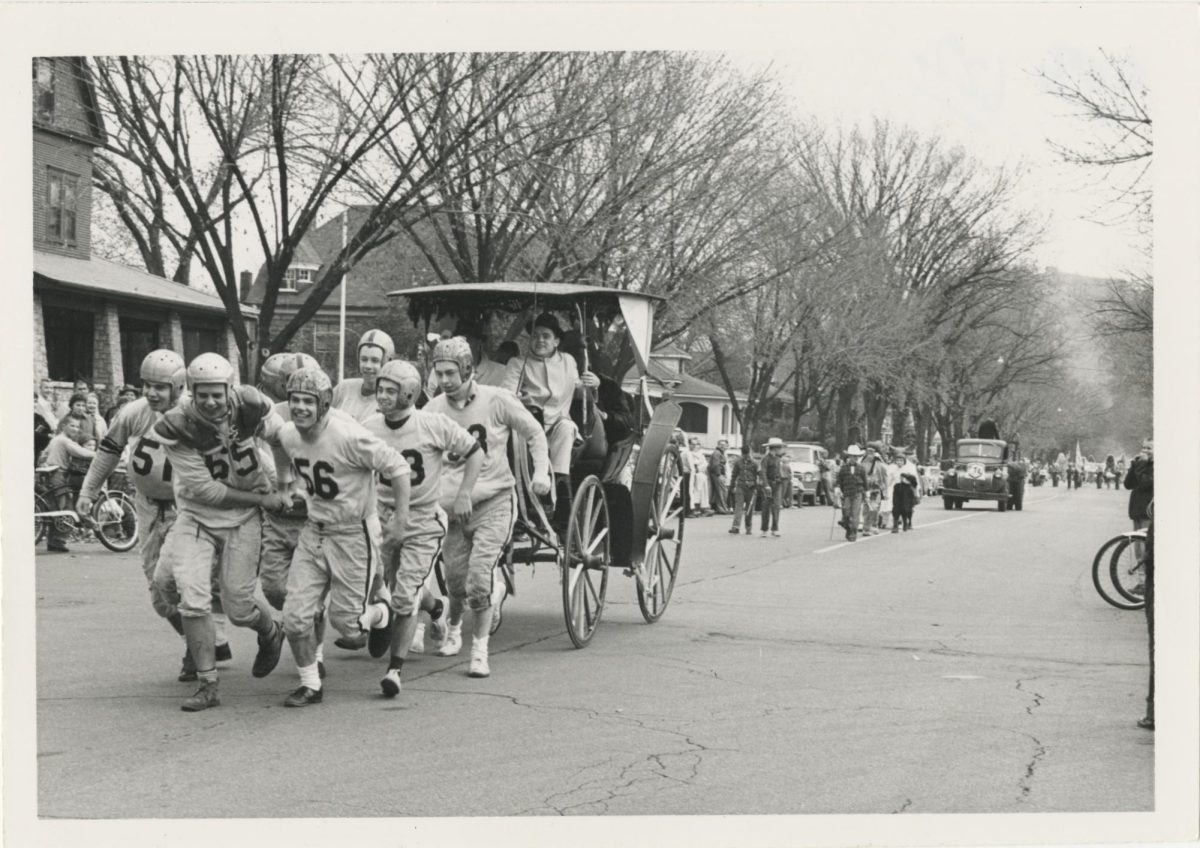

The parade on Saturday morning featured students who dressed as hobos, bums and clowns, which was a homecoming trend that spread across the Midwest in the 1920s according to an article by the Wisconsin Alumni Association.

Businesses and residents of La Crosse decorated their homes and windows to embolden the school spirit for homecoming. The school even put on a contest for the best decorations, and this continued in the following years, joined by awards for the best parade float and best costume at the parade.

The university also hosted a bonfire the night before the game. They used an enormous stack of wood and anything else that would burn to create the giant celebratory flame.

“We want every Normal student and every interested citizen in La Crosse to contribute something, anything that will burn and make a blaze. We are going to have a bonfire that will be seen for blocks,” said the 1924 Racquet Press.

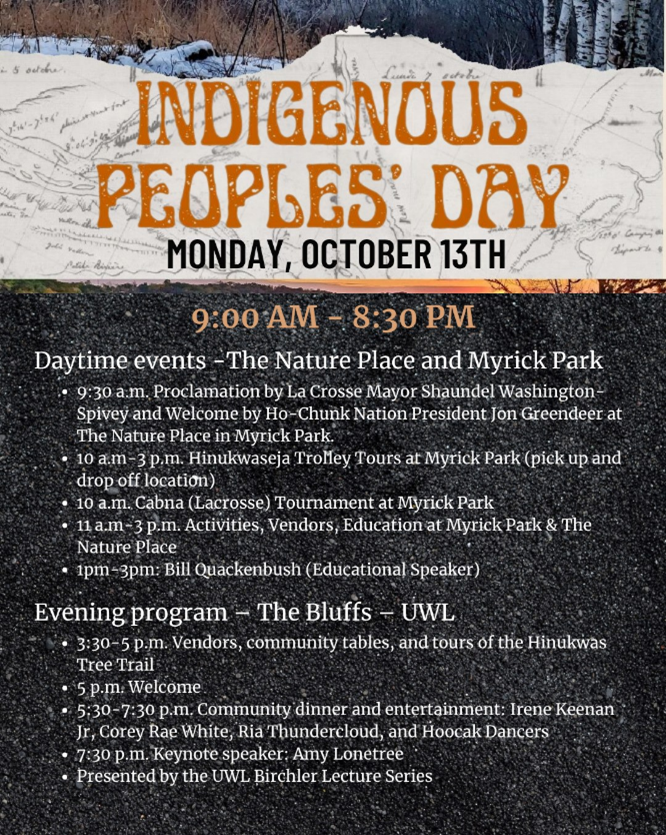

Along with the music and speeches, a snake dance was part of the bonfire festivities.

“A snake dance consists of students holding hands and thus constructing a long line. The line then ‘snakes’ through campus, businesses, and/or outdoor areas,” said Dr. Leslie F. Crocker in his book We’ve Hung the Lantern: A Visual History of the First 50 Years of UW-La Crosse.

The tradition of the snake dance outlived the bonfire, and in 1976 the students of UWL attempted to break the record for the longest snake dance in

the Guiness Book of World Records. The Oct. 21, 1976 edition of the Racquet stated that they fell about 800 students short of the 3,376 record, which still left them with an impressive snake dance of over 2,500 people.

In 1931, one of UWL’s most beloved traditions began. English Professor O. O. White wrote a letter to the alumni and said, “We’ll hang the lantern in the old college tower over the south door. You won’t need to look for the key- the door will be open.”

This was the beginning of the hanging of the lantern tradition here at UWL. For over sixty years the lantern was hung on the south side of Graff Main Hall to welcome alumni home to campus, but in those early years, there was more than just the single lantern hung for homecoming.

“Students were urged to obtain a lantern and display it on Homecoming night as a symbol of brotherhood and mutual affection,” said the 1934 Racquet Press. According to the Nov. 1, 1935 edition of the Racquet, paper lanterns were sold with the proceeds going towards the homecoming expenses, and every student was encouraged to display a lantern in their window.

“Displaying the lantern should give everyone personal pride and be considered a privilege, not an obligation,” White said in the 1934 Racquet. “That which this paper lantern symbolizes may mean more to you than all the material things of life as you grow older.”

According to the Nov. 9, 1951 edition of the Racquet, the original lantern hung outside of Graff Main Hall was not made of paper but made of beaverboard. It was replaced in 1947 by a sturdier metal lantern which continued to be hung outside of Graff Main Hall. The current lantern was permanently moved into the Hoeschler Clock Tower in 1997.

Another homecoming tradition that continues today is the Lighting of the “L”. This tradition began back in 1935 and was sponsored by the “L” Club, the same club that started and continued to run UWL’s homecoming celebrations.

“Between the halve[s] of the game Saturday night, the “L” Club will light a huge “L” on Miller’s Bluff. The letter will be nine feet in length and should show up very well to the people in the bleachers,” said the 1935 Racquet Press.

The first “L” was made of brush, and according to Dr. Crocker’s book, roommates F. Clark Carnes and Bernie Brown were the ones to light it. They used their room and board money to fill two five-gallon cans of gasoline and climbed up the bluff to light the brush-shaped “L” on fire.

Carnes and Brown were rushing because the police had been alerted to their plan, and in the process of pouring the gasoline on the brush, they coated themselves in it. As the sirens drew closer, Carnes and Brown considered abandoning the stunt.

The roommates were covered in gasoline, and if they managed to light the brush without igniting themselves, it was an incredibly foggy night. In the current conditions, no one would be able to see the “L” from the football field.

Carnes and Brown just decided to go for it and lit the “L” on fire, hurrying down the bluff, evading the police and returning to the football game at halftime. The fog began to lift, and the burning “L” was revealed to the homecoming crowd.

According to the Oct. 30, 1936 edition of the Racquet, the “L” burned again the next year, this time on Grandad Bluff, and it has been lit on top of Grandad Bluff ever since.

“On the bluff between the halves, twenty-eight torches burning a fierce red “L”, seeming to hang on air high above the earth,” said the 1937 Racquet Press.

This was a new version of the “L”, described by the Oct. 8, 1937 Racquet Press as a large wooden frame with flares inside.

After the 1930s, there was a period of time when the “L” was not lit. According to the Oct. 21, 1949 edition of the Racquet, this changed in 1949 with a revival of the “L” paired with a fireworks show.

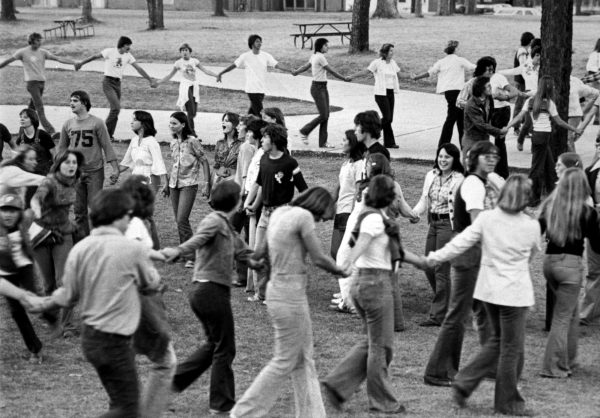

After the burning brush “L” and flare “L”, the “L” was created by burning kerosene-soaked rags in coffee cans, according to Dr. Crocker’s book. Later, this was exchanged for an electric “L”. There have been a few versions of the electric “L”, one with lightbulbs on a frame, and newer versions made with colorful Christmas lights.

The current “L” lights up Grandad’s Bluff at the beginning of the fall semester to welcome students to campus, and is also displayed at the Rotary Lights in Riverside Park during the holiday season.

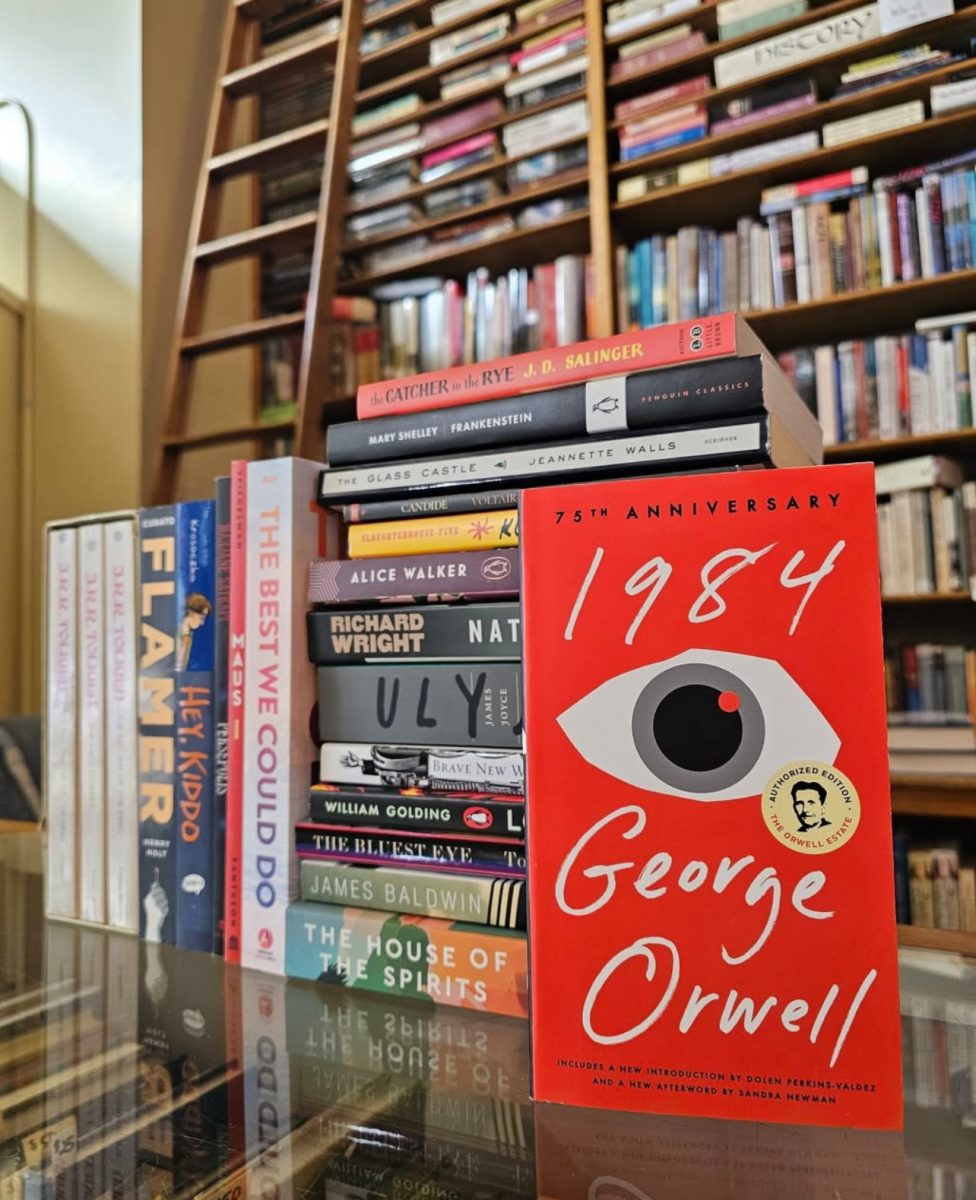

Another UWL homecoming tradition is the rushing of the theater. In 1934, the year before the first L burned on the bluff, a few students headed downtown after the homecoming pep rally.

“In working off some of their exuberance, they [a group of UWL students] broke a door in one of the local theatres,” said the 1934 Racquet Press. “Instead of trying to ‘crash’ in, let’s try to arrange for a legitimate theatre party for next Homecoming.”

This was the birth of rushing the theater, a tradition in which students would head downtown for a theater party and movie viewing at the Rivoli after the bonfire on the night before the football game.

“Snake dancers will wind their way around the fire until the mammoth fire begins to die and then the dancers will head for the downtown district where they will be the ‘guests’ of one of the local theaters,” said the 1939 Racquet Press.

In 1937, the first homecoming queen was crowned. According to the Oct. 8, 1937 edition of the Racquet Press, the homecoming queen was chosen by the student body.

Ten women were nominated, and votes were cast. The queen and her court were announced at the dance, and the court was made up of the five runners-up of the homecoming queen.

In the years that followed, the homecoming queen was usually featured on the front page of the Racquet Press and joined by articles about the homecoming festivities.

In 1943 and 1944, amidst World War II, there was no football team at UWL since most of the men were involved in the war. However, according to the Oct. 13, 1943 edition of the Racquet, homecoming prevailed with many of the same traditions in the absence of football.

Instead of football, the women’s field hockey game was the highlight of the weekend. The UWL seniors played the school alumni every year on homecoming weekend as part of the festivities, but for the 1943-44 homecomings, the hockey game helped to carry the homecoming celebration through wartime at UWL.

Homecoming at UWL prevailed through WWII and continued until the end of the century. Activities and traditions changed throughout the years, but almost every year, homecoming was promised to be bigger and better than ever.

Today, this is not the case. An Oct. 9, 2017 article of the Racquet goes into detail about how it was difficult to juggle Oktoberfest, Family Weekend and Homecoming. The article also stated that people were not as interested and enthusiastic about the events hosted for homecoming weeke

nd anymore.

“We had pep fests. We had parades except none of the students came out of the res halls to support their fellow students,” said Executive Director of the Alumni Association Janie Morgan in the 2017 Racquet Press.

Today the football schedule lists homecoming as a part of Family Weekend. There is still a football game, and a free movie is held in the Student Union, similar to the movie and theater party at the Rivoli back in the day. However, there is no more parade, bonfire or dance to celebrate homecoming at UWL.

The lantern hangs in the clocktower, and the “L” still lights up Grandad’s Bluff, but today traditional homecoming at UWL is no more.

“But there is no homecoming as wonderful as that when you come back once more to the halls where you learnt to love your Alma Mater. You’ll be greeted with a hearty handclasp and an arm thrown around the shoulder. Your heart will almost burst. It’ll be full to overflowing. For there is no friend like an old friend, and you’ll meet him at Homecoming,” What Homecoming Means, the 1924 Racquet Press.