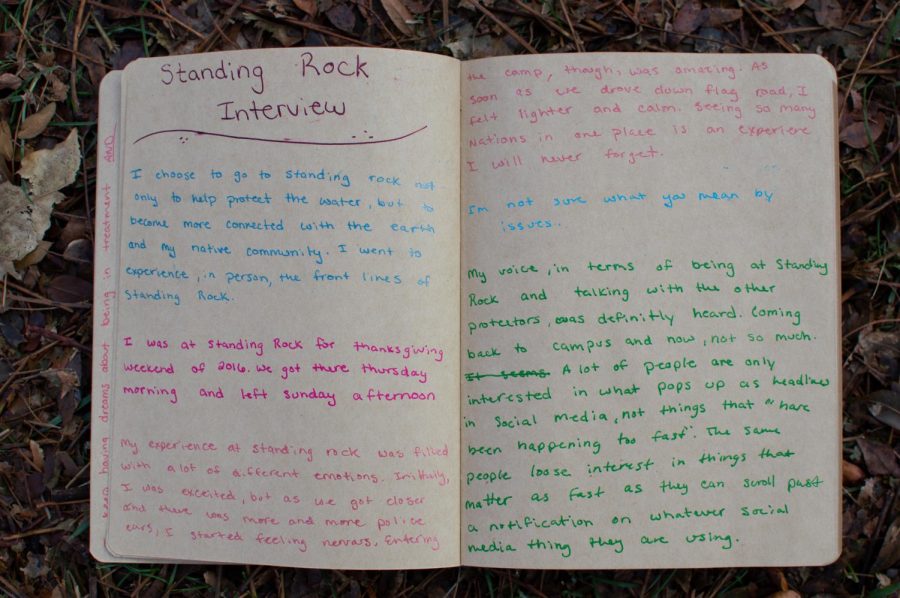

Photo Series: UWL student recounts experience at Keystone Pipeline protests

December 8, 2019

In an interview with The Racquet Press UWL student Katheryn Horne recalled her experience from the 2016 Keystone Pipeline protests at Standing Rock.

The Racquet Press: Why did you choose to go to Standing Rock?

Horne: “I chose to go to Standing Rock not only to help protect the water, but to become more connected with the earth and my native community. I went to experience, in person, the front lines of Standing Rock.”

The Racquet Press: How long were you there?

Horne: “I was at Standing Rock for Thanksgiving Weekend of 2016. We got there Thursday morning and left Sunday afternoon.”

The Racquet Press: What was your experience like?

Horne: “My experience at Standing Rock was filled with a lot of different emotions. Initially, I was excited, but as we got closer and there was more and more police cars, I started feeling nervous. Entering the camp was amazing. As soon as we drove down Flag Road, I felt lighter and calm. Seeing so many nations in one place is an experience I’ll never forget.”

The Racquet Press: Did you feel like your voice was heard?

Horne: “My voice, in terms of being at Standing Rock and talking with the other [water] protectors, was definitely heard. Coming back to campus and now, not so much. A lot of people are only interested in what pops up as headlines in social media. The same people lose interest in things that matter as fast as they can scroll past a notification on whatever social media thing they are using.”

The Racquet Press: Did you ever feel like you were in danger? What was your experience with the police and military forces? Did you feel they were keeping you safe?

Horne: “Standing by Turtle Island, I didn’t necessarily feel like I was in danger, but I definitely felt intimidated and devalued as a human. There was barbed wire across the bottom of the island and all the canoes on the side of the water were destroyed. There were police on top of the island and they all had guns and just watched. One of the police, kneeling, would move his gun back and forth, kind of scrolling past the beach where we were standing. Whether or not they were guns with real bullets or rubber bullets I do not know. The police were not there to keep or make us feel safe. They were there to intimidate, scare, and ‘keep us in line’.”

The Racquet Press: Knowing what you know now, would you still have gone to Standing Rock?

Horne: “Knowing what I know now I would have gone sooner and stayed longer. I wish I never would have left. Being there was one of the most influential experiences I will probably have. Being able to be fully surrounded by people who know what it’s like to be Native (and who are Native). Yes, I have a great community on campus and at home, but being in the middle of over 200 different indigenous nations was nothing short of amazing.”

The Racquet Press: Why is Standing Rock still important today?

Horne: “It’s already leaked three or four times and now there’s been a huge leak. It doesn’t just affect the native community it affects all of us living here, but no one wants to address that. They want to say ‘Oh the natives are up and yippity about it because it’s on their land’, but this is affecting you too. You just don’t care. Being a Native on this campus and everywhere within what is currently known as the United States and probably the world — my pain, my hurt, my oppression is up for debate. As a white passing Native, especially on this campus, I have to prove that something someone said in terms of my identity, hurt; I have to prove that I’m Native; I have to prove all these things that make me who I am, because the white person gets to dictate whether or not I am those things.”